Mid 1700s

People of the Grand

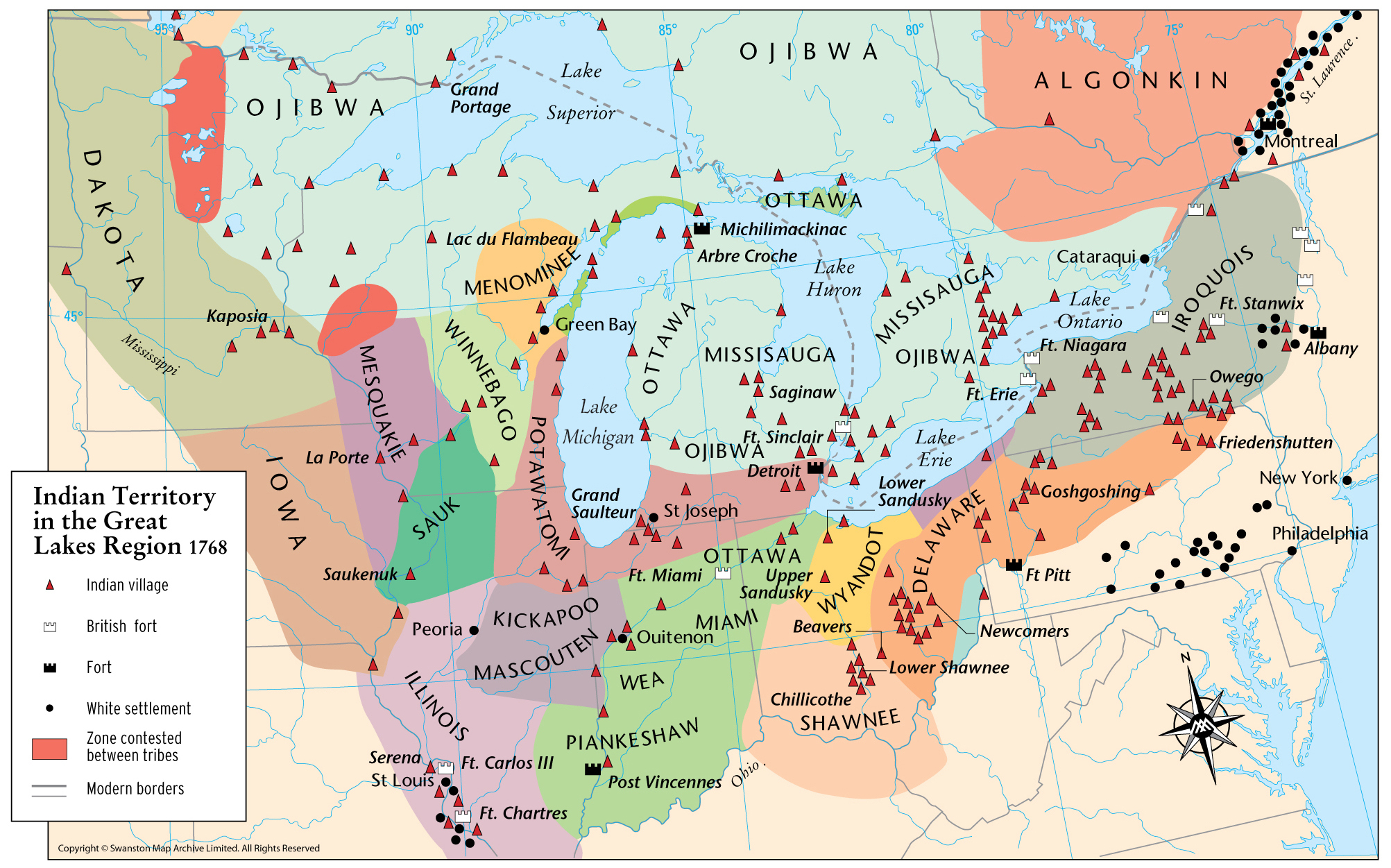

The Anishinaabe lived on the banks of the Grand River long before the first white settlers arrived from the east. “Anishinaabe” is an Indian langauge word meaning “the people,” to which the Ottawa (Odawa), Chippewa (Ojibwe) and Potawatomi (Bodewadmi) referred to themselves.

They called the Grand River “Owashtenong,” which means “the-far-away-water,” because it was the longest river in the territory.

Owashtenong provided bountiful fishing and game, supporting a large population, and served as a major transportation route for trade. Indeed, the word Ottawa (Odawa) derives from the Indian language word that means “to trade.”

![“People of the Grand,” by Robert Bushewicz (Chief Preparator of Exhibits, Grand Rapids Public Museum), circa 1980. [Mural Painting]](https://mckaytower.com/media/Along-Banks-of-Grand-River-GRPM-1.jpg)

During this era, the Grand River Valley was governed and controlled by a regional confederation of 19 Ottawa (Odawa) bands later referred to as the Grand River Bands of Ottawa. The Grand River Bands of Ottawa (“Grand River Ottawa”) had multiple villages located on the Grand River and on various tributary rivers of the Grand as well as other rivers in western Michigan encompassing the territory just north of the Kalamazoo River up to the Manistee River. The Grand River Ottawa shared jurisdiction over lands south of the Grand River with the Potawatomi.

![“People of the Grand,” by Robert Bushewicz (Chief Preparator of Exhibits, Grand Rapids Public Museum), circa 1980. [Mural Painting]](https://mckaytower.com/media/Along-Banks-of-Grand-River-GRPM-2.jpg)

In the mid-1700s, what is now the City of Grand Rapids was home to two Ottawa villages that were located on the west side of the Grand River separated by a quarter mile.

The first, known as Muckatosha’s Village, was located about a quarter-mile below the rapids, in the neighborhood of what is now West Fulton Street, where Watson Street SW and Mt. Vernon Avenue SW intersect. In the late 1700s to early 1800s, Muckatosha’s Village was said to have an average population of 700.

The second village, known as Bowting (meaning “the rapids”) was near the bottom of the rapids and was led by the Ottawa Chief Nowaquakezick (a.k.a., Noonday) and had a population of about 500.

The Grand River Ottawa maintained gardens and other improvements at these villages and, in the winter months, traveled to traditional hunting and trapping camps in the southern and northern parts of their Territory.

Prior to 1790, the Grand River Ottawa sought to maintain control of their territory and the resources in their lands by fostering trading relations with the French, the British and the new Americans.

1795

The Treaty of Greenville

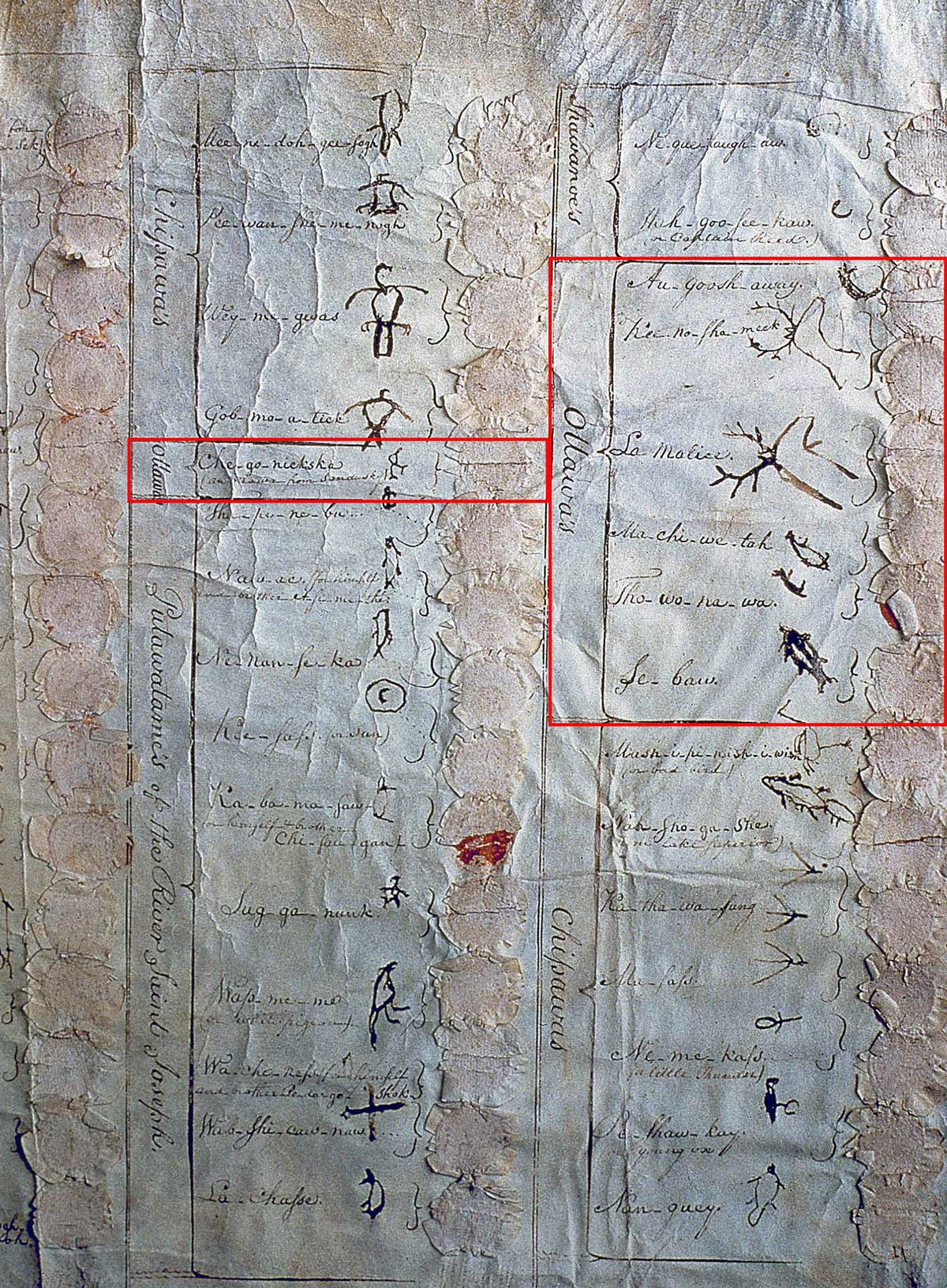

Between 1795 and 1855, the Grand River Ottawa were parties to several treaties with the United States government, the first being the 1795 Treaty of Greenville.

The Treaty of Greenville was a treaty of peace that resolved a war in which the Grand River Ottawa had allied themselves with the British against the United States.

Among other things, the Treaty of Greenville: 1. Established the boundary between the United States and Indian Nations 2. Opened trade between the United States and the Indian Nations and 3. Regulated the conduct of non-Indian persons entering Territory of the Indian Nation signatories.

1821

The Treaty of Chicago

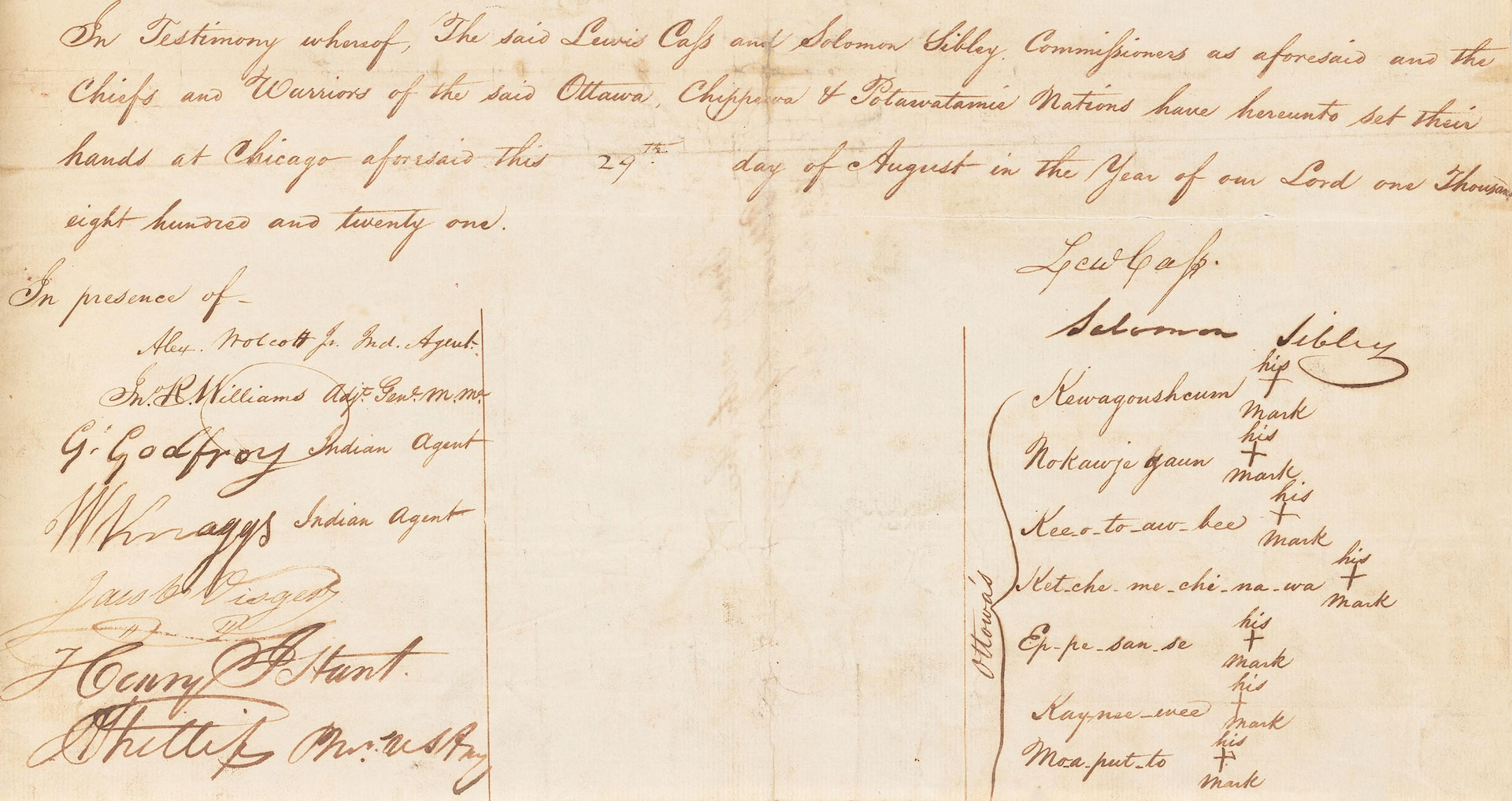

Not long after the Treaty of Greenville, the United States government sought concessions of lands by Michigan tribes to meet the demands of settlers.

The Treaty of Chicago was negotiated to seek a cession (sale) of land that included the Grand River Ottawa lands south of the Grand River and a large portion of the Potawatomi lands in southwestern Michigan, but retained hunting, fishing and gathering rights in the lands ceded.

Although most Grand River Ottawa chiefs and headmen opposed the sale of lands to the U.S., a few chiefs agreed to sign the 1821 Treaty.

Despite the objections of most Grand River Ottawa leaders, the U.S. government considered the treaty valid and enforced its terms. The primary Chief approving the treaty, Keewaycooshkum from Prairie Village near the confluence of the Grand and Rogue Rivers, was widely condemned for acting outside his authority and was reportedly either exiled to the Manistee River or executed as a result of his actions.

Under the terms of the Treaty, the U.S. government was to furnish the Grand River Ottawa with a teacher, blacksmith, cattle, metal tools, oxen, plows to clear the land, government-supplied provisions and other resources to be located upon a square mile of land for mission purposes for 10 years; however, due to opposition from Chief Muckatosha, who opposed the Treaty’s validity, implementation of these terms was delayed.

Finally, at the request of Chief Nowaquakezick, Isaac McCoy established the first Baptist mission in 1826 on the west side of the Grand River, at the foot of the rapids, near Chief Nowaquakezick's village.

One possible reason why Chief Nowaquakezick was so friendly to McCoy could have been that he was trying to protect his people from a future dominated by Americans by securing access to the resources and political support provided by the mission.

1826

Grand River Settlement

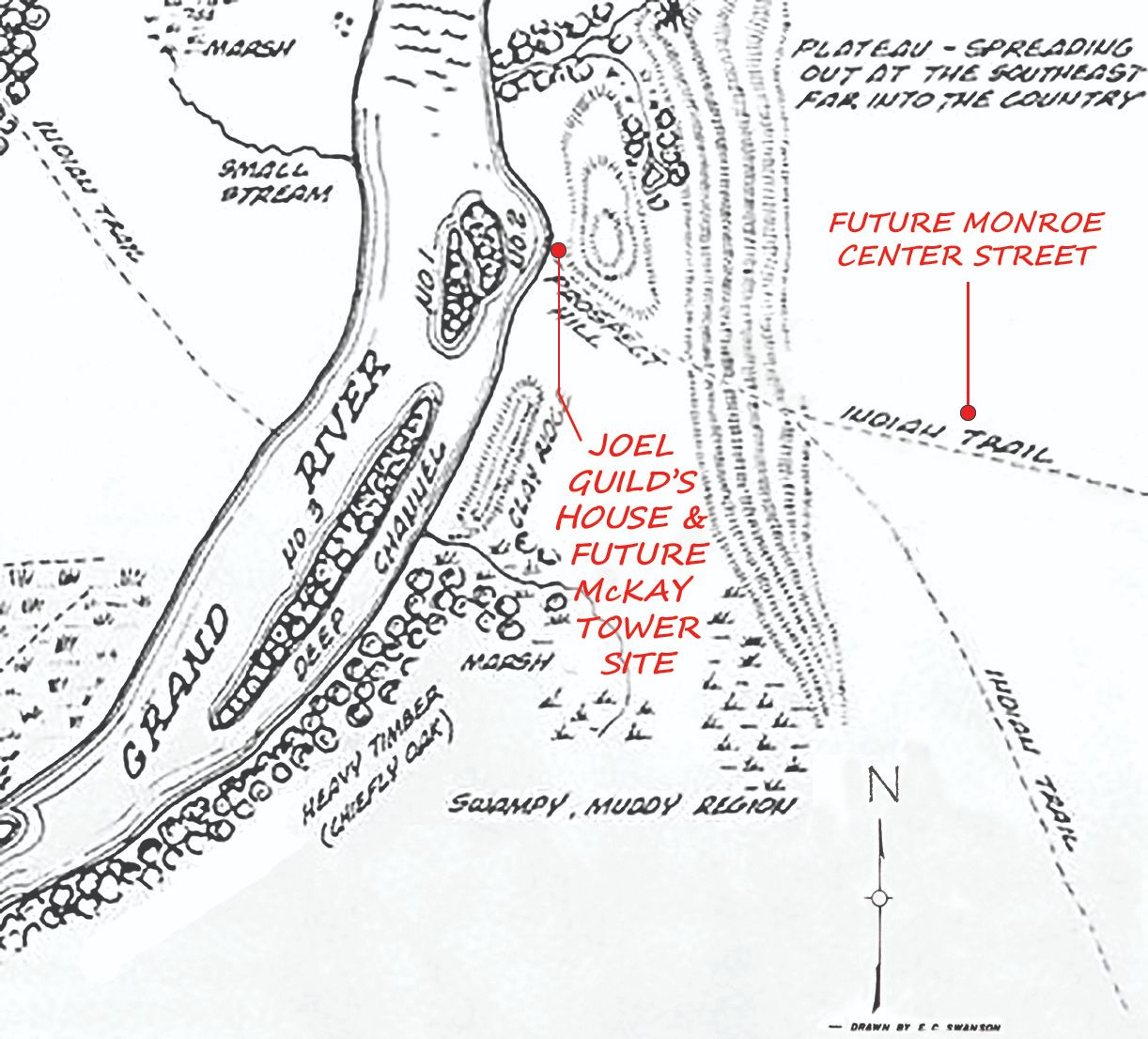

In November 1826, Louis Campau and several other French-speaking individuals settled on the east side of the Grand River, opposite the mission, and began operating a trading post with the Native Americans of the area. Campau was reported to have had an excellent relationship with Chief Muckatosha, who aligned his Village with Catholic missionaries.

1827

By 1827, McCoy’s mission compound was 160 acres and had several log houses (some with plank floors and glass windows), a sawmill financed with Treaty funds, a farm, agricultural tools and fenced pastures for the 55 head of cattle supplied by the government to begin Ottawa herds. Living on the premises were non-Indian farmers who were to teach the Ottawa "American-style" agriculture practices, carpenters to build their houses and a missionary, Leonard Slater, to minister to their spiritual needs and supervise mission operations.

Ottawa people from other villages, including Muckatosha’s, made similar efforts to adapt to the new political and economic realities in order to retain control over their homelands.

1833

The Guild Family

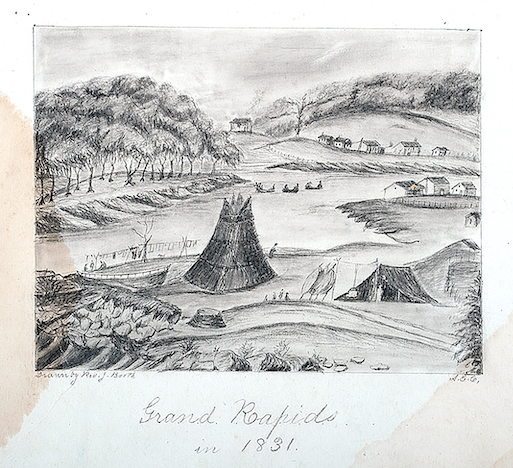

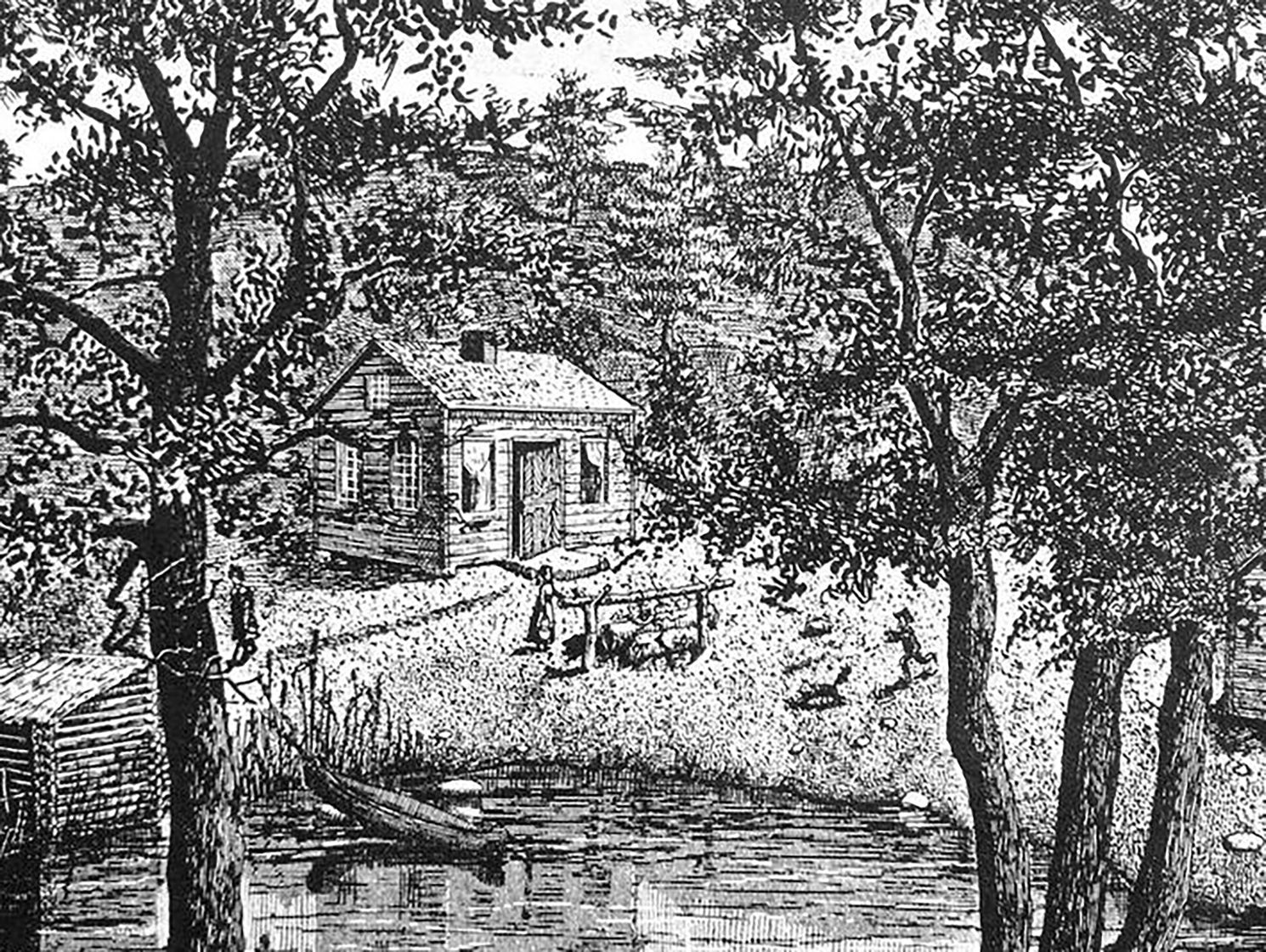

In 1833, Joel Guild moved his family from New York to Grand Rapids, purchasing the site of the present-day McKay Tower from Louis Campau for $25. It took Guild roughly 10 weeks to build his 16 x 26-foot house. It was the first frame house in Grand Rapids, and the lumber for it was produced at the sawmill located on the Ottawa Mission. Guild and his family moved into the house on Aug. 31, 1833.

1834

Joel Guild held the first township election, consisting of only nine voters, at his residence on April 4, 1834.

As new settlers persistently moved into the Michigan Territory and continued encroaching on Grand River Ottawa lands, pressure built to seek another large cession of land from the Grand River and other Ottawa and Ojibwe Bands to the north.

Knowing the Grand River Ottawa in particular were opposed to further land cessions, the United States negotiators brought the delegation of chiefs and headmen from the Ottawa and Ojibwe Bands to Washington, D.C., to conduct these negotiations under circumstances intended to pressure those leaders away from the support of their communities.

The resulting cession of lands in the 1836 Treaty of Washington dramatically changed the lives of the Grand River Ottawa.

Grand River Ottawa village sites and homes were quickly claimed by new settlers and land speculators. The 1836 Treaty also included language which contemplated that the Grand River Ottawa would relocate on lands that were not sold (were “reserved”) by the Ottawa – a reservation on the Manistee River.

Most Grand River Ottawa refused to leave their homes along the Grand River. A large number, however, were forced to leave their homes and improvements behind, including those the Baptist Mission helped them establish. For this reason, a number of Grand Rapids settlers received ready-made houses, farms and even a working sawmill, all at Ottawa expense.

The Ottawa did not sit idly by and let the new settlers run their affairs. They actively worked to make a place for themselves in the new American economy. They also used annuity money from the cession of their lands to purchase property that became available in and around their former villages as it came on the market for public sale.

As Indians, they were still subject to treaty provisions, including the clause contemplating their removal to a reservation on the Manistee River; however, as landowners, they had unchallengeable rights to enjoy the use of their property, which implied the right to remain in Michigan and prevent a future that involved permanent removal.

1852

The Evolution of Guild’s Property

A daguerreotype photo of “Grab Corners,” later called Campau Square in Grand Rapids. On the right, circled in red, a dark swinging sign of a bull denotes a meat market in the building that Joel Guild constructed as his first village residence in 1833.

Sometime after 1852, Joel Guild’s house was replaced by a small frame building occupied by Joseph Houseman, father of Henry L. Houseman of the former clothing firm Houseman and Jones that used to operate on Monroe Center Street. A short time after, a two-story frame grocery store operated by Alma Bradford was built. Then, a small frame building used by David S. Berry as a saloon and restaurant with a gambling annex was built.

1855

The Treaty of Detroit

Part of the Ottawa’s efforts involved negotiation of a new Treaty, the 1855 Treaty of Detroit, which was intended to provide a permanent homeland by reserving lands for the Grand River Ottawa in what are now Muskegon, Oceana and Mason Counties.

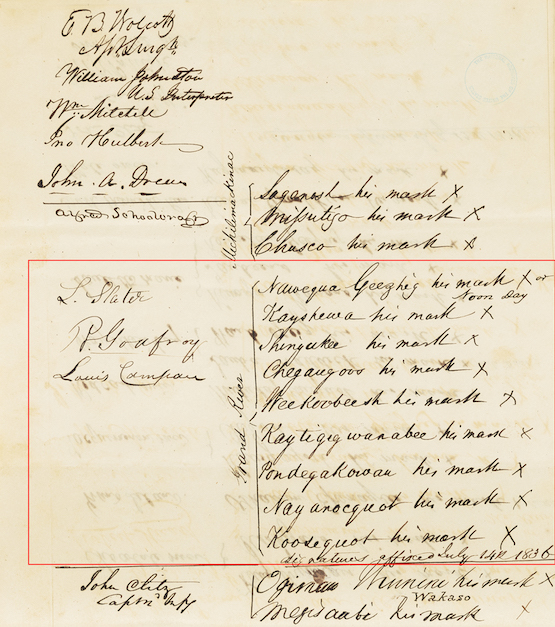

One of the signature pages from the 1855 Treaty of Detroit, including Chief Maish-Ke-Aw-She, of which Ronald Yob, the current Tribal Chairman of the Grand River Bands of Ottawa Indians, is a direct descendent.

Unfortunately, the terms of that Treaty were never fully, nor properly, implemented by the United States and many Grand River Ottawa families were denied lands in those reservations.

As a result of these dynamics, Grand Rapids has since Treaty times continued to have a significant population of Grand River Ottawa people who continue to advocate for the rights and interests of the Grand River Bands.

1865 - 1914

The Changing Face of Campau Square

On Feb. 17, 1865, the City National Bank was formed. It was built sometime in the mid-1860s on the corner of Monroe and Pearl.

At some point between the years of 1873-1874, the smaller buildings at Campau Corner were removed. These two buildings were McGowan Brothers Meat Market, owned by Almeron & John McGowan, and Remington’s Custom Shirts.

In 1874, Earner Nellis and James L. Moran, the latter being Grand Rapids’ first superintendent of police, designed and built what would become the Wonderly Building.

Sometime in 1881, both Nellis and Moran passed away. Their widows sold the building to James H. Wonderly, who renamed it after himself and eventually added two stories.

In 1890, J.H. Wonderly worked with architect Sidney J. Osgood to renovate and beautify his six-story building to include two towers.

1914

The Grand Rapids National City Bank

In 1914, the Grand Rapids National City Bank (an entity created between the 1910 merger of the Grand Rapids National Bank and the National City Bank) acquired the Wonderly Property with the intent of running both itself and its auxiliary, the City Trust and Savings Bank, in one large building facing Campau Square.

The bank and the Wonderly Building were both demolished in 1914 to pave the way for the first four stories of the current McKay Tower structure.

Construction of the new building was slated to begin on July 1, 1914. It was designed in such a style to imitate the “new Chicago banks” of the era.

The Grand Rapids National City and the City Trust and Savings Banks began occupying their new home the following June.

1925

Construction of the Tower Begins

On Oct. 1, 1925, construction work was scheduled to begin for the next 14 stories of the renamed Grand Rapids National Bank’s new tower. It was estimated that 600 tons of steel would be required for this new addition.

.jpg)

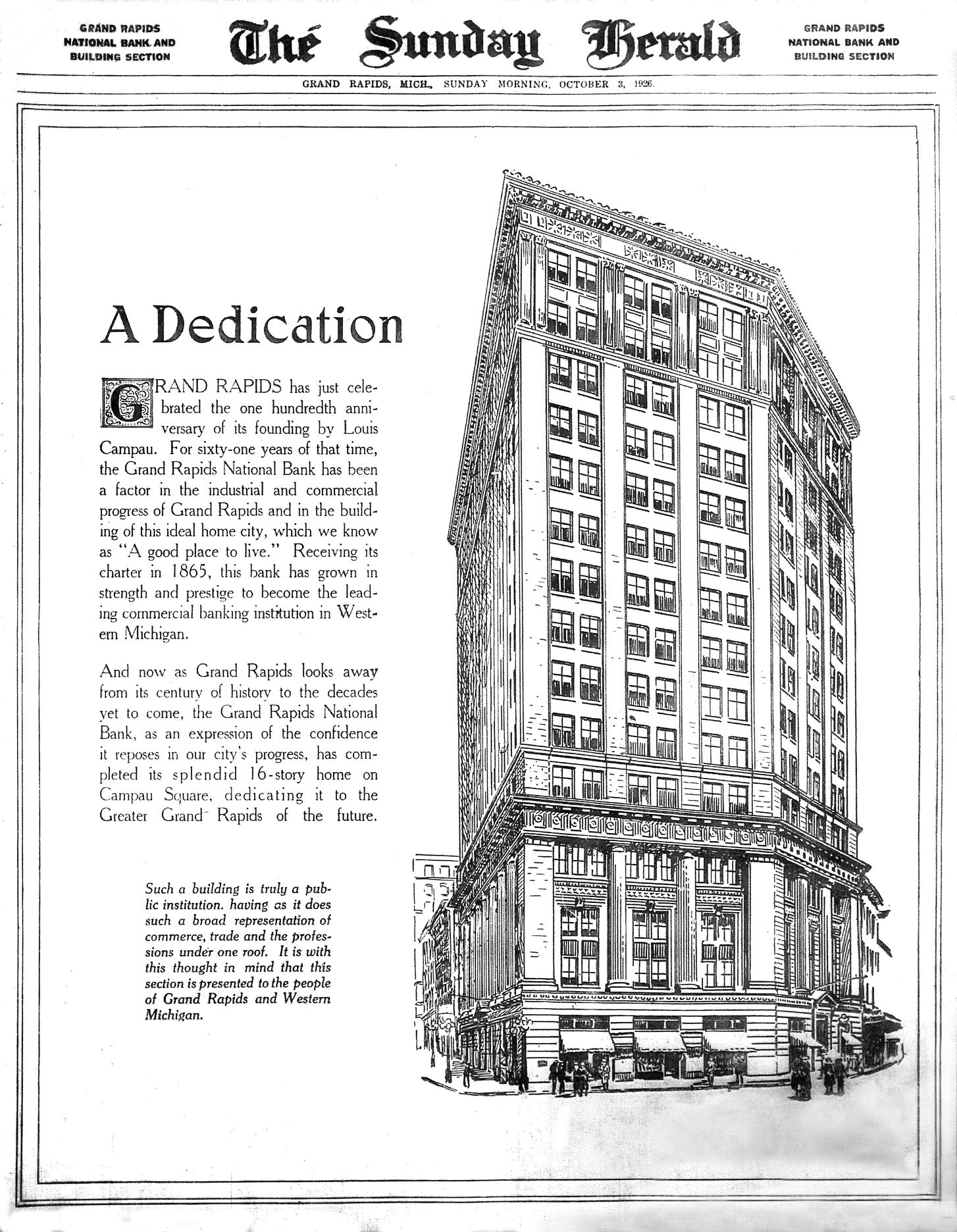

1926

Greater Grand Rapids of the Future

On Oct. 3, 1926, in a special section of The Sunday Herald, the Grand Rapids National Bank dedicated its newly completed tower to the “Greater Grand Rapids of the future.”

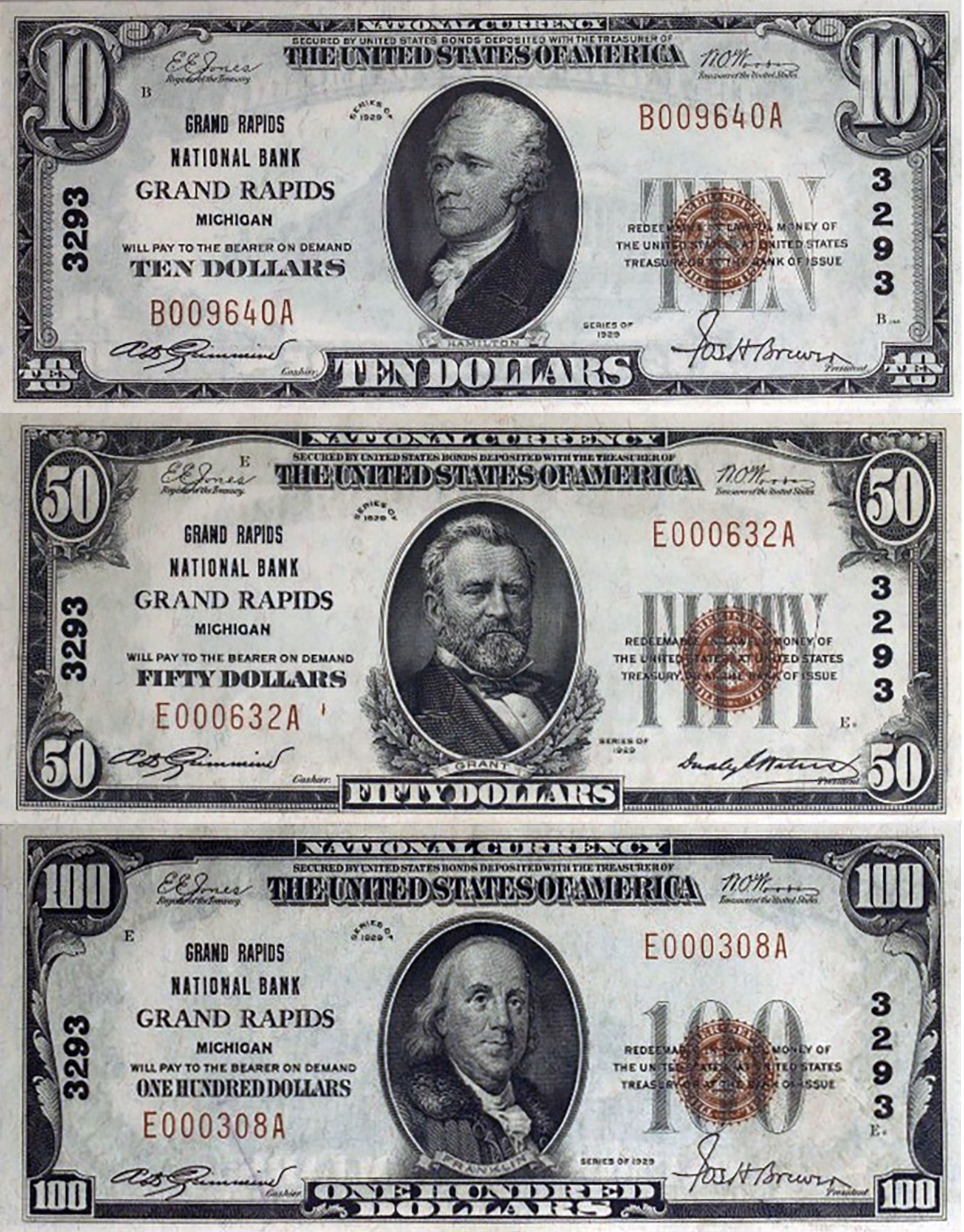

In 1929, the Grand Rapids National Bank utilized the authority of The National Banking Act of 1863 (and subsequent legislation) to print national currency.

1930

The Great Dome

On April 19, 1930, the Grand Rapids National Bank lit its new “great dome of red light” for the first time. At the time, it was thought to be the largest neon-lighted beacon in the United States. It cost $18,000 to install and was projected to cost $55 per month to operate.

1933

The Great Depression

In March 1933, the Grand Rapids National Bank failed because of the Great Depression. It was one of six banks in the city that was forced into reorganization or liquidation. The National Bank of Grand Rapids was established in the tower in 1933 after the failure of the Grand Rapids National Bank, and reportedly closed 2 years later.

1942

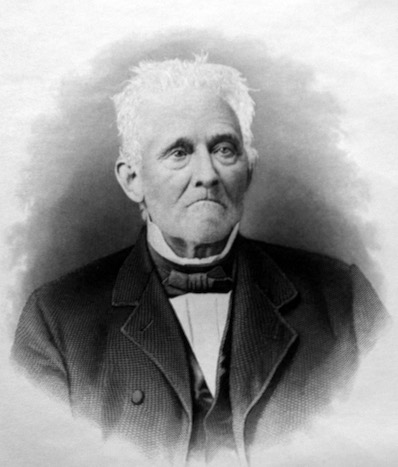

Frank McKay

In 1942, Frank McKay, a well-known businessman and State of Michigan Treasurer (1925-1931) purchased the former Grand Rapids National Bank building. Sometime between 1953 and 1956, he renamed the building "McKay Tower."

When Frank McKay died in 1965, he willed his tower to the University of Michigan. In 1986, the University acquired full ownership under the terms of the McKay wills.

2000 - 2012

New Owners

When the economy was right in the year 2000, the tower was sold to Greystone Associates of Skokie, Illinois, so that the university could gain the most for the property and put the proceeds into an endowment for medical research, as the late Frank McKay intended.

In April 2006, Mark Roller of Spring Lake purchased McKay Tower through McKay Tower Partners, LLC.

In May 2012, Jonathan L. Borisch, principal with Steadfast Property Holdings, LLC, purchased McKay Tower.

2012

The Ballroom

At the end of 2012 and early into 2013, Borisch renovated the former Grand Rapids National Bank lobby and converted it into the Ballroom at McKay.

2013

A Brighter Beacon

On Aug. 10, 2013, Borisch decided to restore the historical dome on top of McKay Tower, replacing the screw-in incandescent bulbs with roughly 1,200 small LEDs capable of glowing in a variety of colors and patterns as well as producing multiple color-changing effects and animated images.

2020

Gun Lake Investments and Waséyabek Development Company

On Jan. 15, 2020, the Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians (a.k.a., the Gun Lake Tribe) and the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi (NHBP) purchased McKay Tower. The acquisition represents a rare co-investment by the non-gaming economic development entities of two Michigan Native American tribes (Gun Lake Investments and Waséyabek Development Company, respectively).

Michigan’s Mergers and Acquisition (M&A) community recognized the significance of the McKay Tower acquisition by awarding GLI and WDC with the 2021 MiBiz 8th Annual Mergers and Acquisitions Real Estate + Development Deal of the Year!

Present Day

We are proud of McKay Tower and its celebrated history.

We are honored to be stewards of this iconic property and pledge that it will continue to light up the Grand Rapids skyline, leading the way for generations to come.

Interested in learning more about McKay Tower's history?

Check out our in-depth PDF.